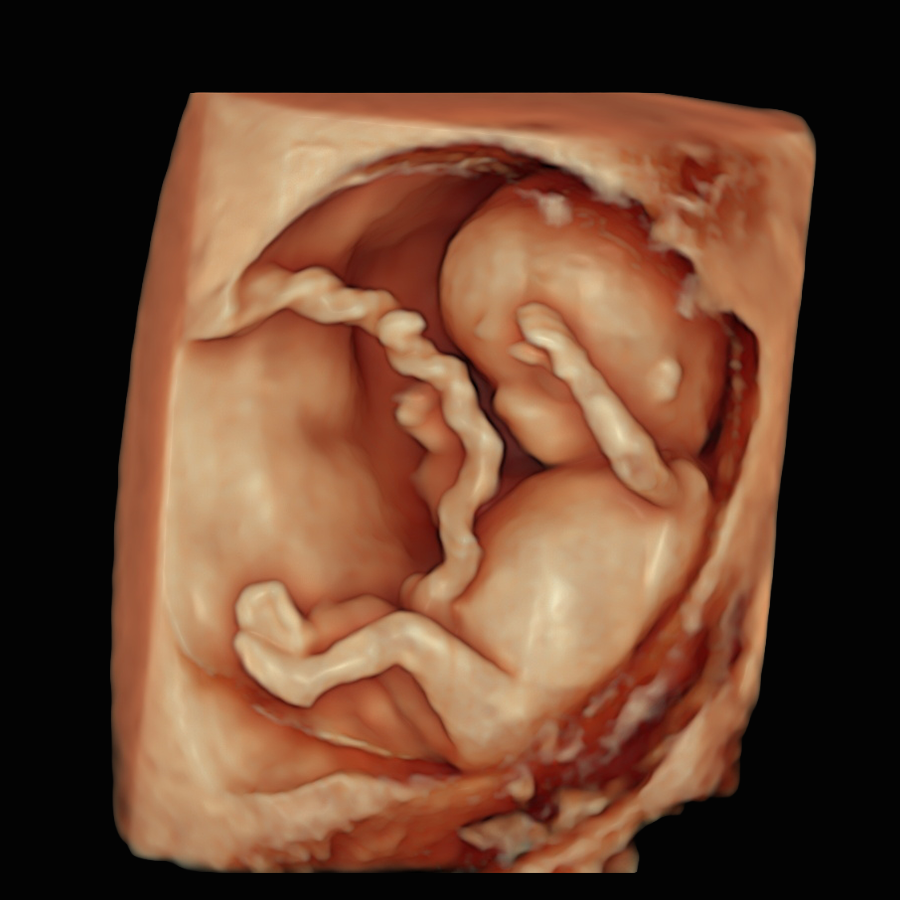

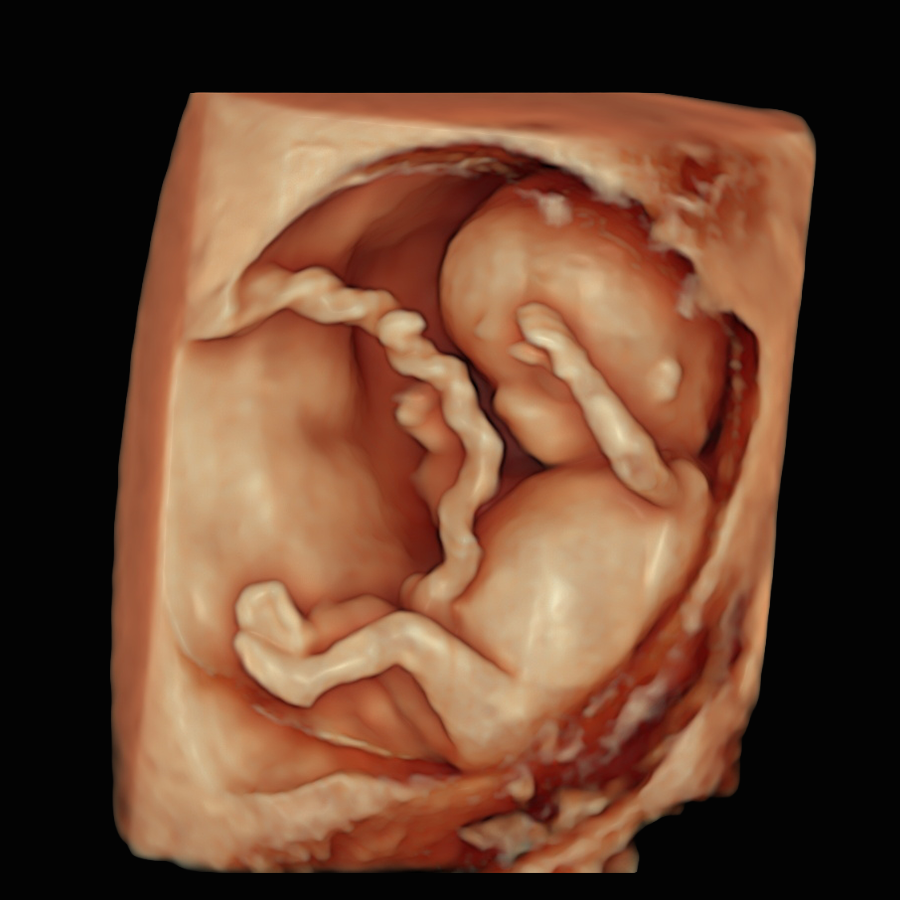

The period between 11 and 14 weeks, when the fetal crown–rump length (CRL) measures 45–84 mm, is the standard time for NT measurement

Chat with our Genetic Counsellor, receive your at-home DNA kit with a quick cheek swab, send it back, and get your results in under 4 weeks.

It is estimated that around 1.4 million babies worldwide each year have an NT above 3.5 mm. This is a huge clinical and emotional burden for parents and professionals. Current management pathways for this problem are largely based on protocols developed at the end of the previous century and are no longer fully up to date. There is an urgent need for modern, evidence-based care pathways that make full use of today’s high-resolution ultrasound and advanced genomic testing, to provide clearer answers earlier in pregnancy.

There are three different periods when nuchal thickness can be measured

At 10 weeks, NT can be measured accurately and may be a more sensitive early sign of possible problems, allowing prompt reassurance or testing.

This is the traditional time for NT assessment as part of the Combined Screening Test (CST). In the UK and many other countries, most babies have their NT measured during this stage of pregnancy.

After 14 weeks, the fluid behind the baby’s neck usually disappears, making the NT measurement unreliable. Instead, a different marker called the nuchal fold (NF) can be measured at this stage.

Increased NT Cut-off day by day chart.

When the NT measurement is combined with your age and blood tests (the “combined screening test”), about 85–90% of pregnancies with Down’s syndrome can be picked up, with roughly 3–5% of results being “false alarms” (high-risk results in pregnancies where the baby is actually unaffected). Using the NT measurement on its own is less accurate, with a detection rate of around 70%.

By comparison, NIPT (using cell-free fetal DNA in your blood) is a much more accurate screening test for the common trisomies, with detection rates above 99% and a very low false positive rate. It also has the advantage that it can usually be performed earlier in pregnancy, from around 10 weeks.

Surprisingly, there is no international consensus on the name for the test combining NT measurement with hCG and PAPP-A to estimate chromosomal chance, and it is known by different names in different countries.

Below is a list of the most commonly used terms:

Combined Screening Test (CST) – UK

First Trimester Screening (FTS) – USA

Combined First Trimester Screening (CFTS) – Australia, New Zealand, Canada

First Trimester Combined Test (FTCT) – Europe

First Trimester Combined Screening (FTCS) – international

Combined First Trimester Test (CFTT) – international

Early Combined Test – Europe

Down Syndrome Combined Screening – outdated

The CST misses about 10–15% of babies with Down syndrome and has a false positive rate of up to 5%. It also has a limited scope, as it screens only for the most common chromosomal conditions (trisomies 21, 18, and 13) and does not detect the wider range of genetic syndromes or structural anomalies.

Overall, it is significantly less accurate and less comprehensive than NIPT.

In some centres of excellence around the world, combined test results are available within 24 hours of the scan and blood test; and sometimes even sooner. This is possible because the NT measurement is available immediately, and PAPP-A and hCG blood results can also be processed within a few hours. However, in most places the laboratory and logistics pathways are more complex, so results typically take longer.

In the UK many units give you a letter or phone call with the combined result within about 1–2 weeks, sometimes sooner. A “high-chance” result is usually communicated by phone, with an offer of an urgent appointment to discuss next steps; “low-chance” results may be sent by post, text or via your maternity app, depending on local practice.

No. A “high-risk” or “higher-chance” result simply means your result has crossed a cut-off (for example 1 in 150) where further testing is recommended.

Combined screening (CST) has a relatively high false positive rate, as many as 1 in 20 results may be labelled “high chance” even though the baby is actually unaffected. So, even with a high-chance result, it is still more likely that your baby does not have the condition than that they do.

Most people with a high-chance screening result will go on to have a baby without the condition, which is why confirmatory tests such as NIPT or diagnostic procedures (CVS or amniocentesis) are always offered.

However, it is important to know that increased NT is also associated with other problems, so additional tests and follow-up scans may be needed.

This is a way of expressing probability. For example, “1 in 100” means that if 100 people had the same result, on average 1 baby would have the condition and 99 would not. In percentage terms, that is about 1% (and 99% that the baby is unaffected).

A smaller second number means a higher probability:

- 1 in 2 ≈ 50% chance (and 50% chance the baby is unaffected),

- 1 in 20 ≈ 5% chance (and 95% chance the baby is unaffected),

- 1 in 1,000 ≈ 0.1% chance (and 99.9% chance the baby is unaffected).

Not exactly. The NT measurement is supposed to be just one part of the scan. The sonographer or doctor should check that the baby is alive, measure the baby to date the pregnancy, and in many cases take an initial look at basic anatomy (head, tummy, limbs and cord insertion).

However, in many countries an “NT scan” does not guarantee that the fetal structure will be properly assessed. For example, in England an audit from 2019 showed that only about 75% of ultrasound units had protocols that included a basic anatomical check at the NT scan, and only around 1 in 8 units routinely examined the structure of the fetal heart.

We strongly recommend that you enquire in advance which structures will be checked in your baby at the NT scan, so you are not faced with unexpected findings, like missing limbs, for the first time at the 20 week anomaly scan.

Absent or undeveloped nasal bone (NB) means that, on the profile view, the small bone in the bridge of your baby’s nose was not clearly seen or looked less developed than expected. Importantly, this does not mean that your baby’s nose is missing or deformed – it is just a soft marker that can be linked with a higher chance of chromosomal conditions, especially Down syndrome.

Because NIPT has a very high negative predictive value for Down syndrome, it is usually an excellent first step to clarify the chances for this condition. In addition, babies with an absent or poorly developed nasal bone should be offered an early detailed fetal scan (by an expert in first-trimester anatomy) to check the heart, face, brain and other structures more thoroughly.

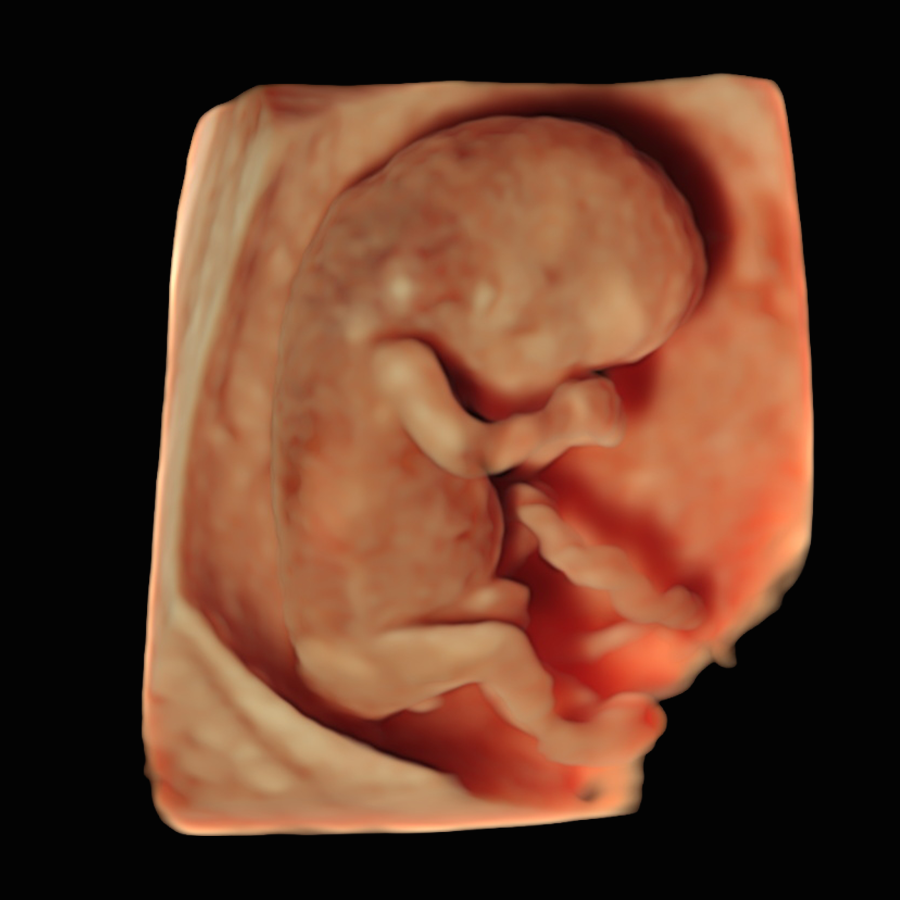

In everyday practice, the vast majority of NT scans are done through the tummy (transabdominally) – in the largest UK study of over 100,000 fetuses, more than 97% were scanned this way. At around 12 weeks the baby usually lies on its back, so measuring NT transabdominally is often straightforward.

However, relying only on abdominal scanning reflects an older view of the NT scan as mainly a test for chromosomal risk. A modern NT examination should also be used as an opportunity to look carefully at the baby’s anatomy. A transvaginal scan (TVS) at 12 weeks offers much higher resolution for fetal structures and is significantly better for excluding structural anomalies, especially if the maternal BMI is high, there are fibroids, or the baby’s position is difficult.

TVS should be offered whenever the practitioner cannot obtain satisfactory views of the baby’s anatomy transabdominally. It is usually not painful (most women describe only mild discomfort, if any) and there is no evidence that it poses any risk to the baby or the pregnancy.

hCG is a hormone produced by the placenta. In the combined test, a “high” hCG usually means your placenta is making more hCG than average for that stage of pregnancy. In the screening algorithm this can increase the calculated chance of Down’s syndrome, especially if it is combined with a low PAPP-A and/or increased NT.

However, markedly raised hCG can also be linked with other conditions, such as molar pregnancy, placental mesenchymal dysplasia, multiple pregnancy, and some serious maternal illnesses (for example severe renal failure). These are uncommon, but if your hCG is very high your doctors will usually arrange a careful ultrasound of the baby and placenta, and sometimes repeat blood tests, to check for these possibilities.

Most women with moderately high hCG have a normal pregnancy, so the result must always be interpreted in context – together with NT, PAPP-A, scan findings, NIPT (if done) and your general health.

Basic NIPT is a very accurate screening test for Down syndrome, Edwards syndrome and Patau syndrome, with no risk of miscarriage, but it is still not 100% diagnostic. Advanced NIPT, such as KNOVA, Vistara or PrenatalSafe Complete Plus, can also screen for certain monogenic syndromes and some microdeletions associated with increased NT, and may have an advantage over standard invasive testing, which in many centres is still focused mainly on chromosomal analysis.

CVS and amniocentesis are invasive diagnostic tests that examine the baby’s chromosomes directly and can usually give a definite answer, but they carry a small additional risk of miscarriage. In some specialist centres it is also possible to look for genetic (monogenic) conditions using exome sequencing or whole genome sequencing (WGS) on CVS/amnio samples, so you should ask specifically whether this is available.

The “right” option for you depends on how quickly you want certainty, how you feel about the small procedure risk, and what you would do with the information. This is best discussed in detail with a fetal medicine or genetics specialist.

In most UK settings and around the world you will still be offered an early scan to confirm the pregnancy location, check how many babies there are and date the pregnancy.

In the UK you can ask the sonographer not to measure the NT or not to generate a Combined Test result if that is your preference; policies can vary slightly between hospitals, so ask your doctor or local team.

In our opinion, measuring NT still has important value because it is strongly associated with heart defects. If the NT is increased, the baby should have a detailed fetal echocardiogram and, if a heart defect is found, specialist care can be planned. Missed heart anomalies significantly increase the risk of the baby dying after birth.

No. Unfortunately, it does not.

A low-chance NT result is very reassuring and means that the chance of the specific conditions it screens for is small, but not zero. Even for Down syndrome, around 10–15% of fetuses with trisomy 21 can have an NT measurement in the normal range and low chance combined screening test.

Importantly, most microdeletions, many genetic (single-gene) conditions, a large proportion of structural problems and even majority of heart defects can be present even when the NT is normal.

To detect these, a detailed early structural scan or later anomaly scan is needed, looking carefully for physical abnormalities. An advanced NIPT panels can also help to reduce the chance of some genetic syndromes that would not be picked up by NT measurement alone.

PAPP-A (Pregnancy-Associated Plasma Protein-A) is a hormone produced by the placenta that plays a key role in supporting the baby’s growth and the health of the pregnancy. It helps regulate important growth factors (IGFs) that promote the development and function of the placenta and the growth of the baby.

By supporting the growth and differentiation of trophoblast (placenta) cells, PAPP-A is essential for healthy implantation and placental function. When PAPP-A levels are lower than normal in the first trimester, there may be a higher risk of complications such as fetal growth restriction or pre-eclampsia (PET) later in pregnancy.

PAPP-A is measured in the routine 12-week screening blood test because it helps doctors assess how well the pregnancy and placenta are developing.

A low PAPP-A result means the level of this placenta hormone in your blood is lower than expected for early pregnancy. It can be a sign that the placenta might not be working at full strength.

Most women with low PAPP-A still have straightforward pregnancies and healthy babies. Doctors mainly use this result as a warning flag to monitor you more closely; it is not, on its own, a diagnosis that something is wrong.

Both PAPP-A and NT are important first-trimester markers, but they reflect different biological processes.

PAPP-A is produced by the placenta and reflects placental health and function. Low levels may indicate poor placental development or chromosomal abnormalities.

NT (nuchal translucency) reflects the baby’s condition, especially the development of the heart, lymphatic system, and connective tissues. Increased NT is linked mainly to chromosomal, genetic, or structural fetal conditions, not directly to placental function.

When interpreted together, PAPP-A and NT help clinicians identify pregnancies at higher risk for chromosomal or structural abnormalities, providing a more complete early assessment of fetal wellbeing.

On its own, a low PAPP-A level does not mean your baby has Down syndrome or any other chromosomal condition. PAPP-A is just one part of the combined screening test. If your overall screening result for Down syndrome and other chromosomal conditions is “low chance”, a low PAPP-A value by itself does not change that. Low PAPP-A is mainly about how well the placenta may be working, rather than about genetic syndromes.

If you are still worried about Down syndrome, non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) is an excellent way to further reduce this concern. NIPT has a very high negative predictive value for Down syndrome – so if the result is low risk, it makes the chance that your baby has the condition extremely small.

Not reliably. The NT scan is not designed to determine sex, and at 12 weeks the genital structures are still too similar to be sure. An expert first-trimester scan at around 13 weeks can suggest the sex with about 95% accuracy (but only in very experienced hands), while NIPT from 10 weeks can usually identify sex with over 99% accuracy.

If the baby is in a perfect position, actually measuring the NT usually takes less than 5 minutes. However, babies often wriggle or lie in an awkward position, so the doctor or sonographer may need more time and might ask you to change position, tilt your pelvis, cough, or even go for a short walk to encourage the baby to move. In many cases a transvaginal scan (TVS) is also needed to get clearer views, which adds a few more minutes.

Checking the baby’s anatomy properly takes longer. If your NT scan includes a structural/anatomical review (which we strongly recommend), you should expect to be in the scan room for around 20–30 minutes, and sometimes a little longer.

Unfortunately, there’s a marked gap between what can be assessed at the 12-week scan and what is routinely checked.

Based on strong, long-standing evidence, two critical and relatively common structural conditions should be screened for at the 12-week NT scan: major congenital heart defects and open spina bifida. Large studies and meta-analyses, some dating back to the 1990s, have clearly shown that many severe heart defects and most cases of open spina bifida already have recognisable ultrasound signs in the first trimester.

Despite this, 25–30 years later, routine screening for these conditions is still not consistently included as part of the NT scan in many places around the world, which often focus only on the chromosomal chance calculation. For this reason, we strongly advise you to ask your antenatal care provider directly whether, at their NT scan, they actively examine the baby’s heart, brain and spine for early signs of congenital heart disease and spina bifida, rather than just measuring the NT.

Our team of experts is here to help. We're just a message away.